In 1966, I was fourteen, and in third year at secondary school. I was quite good at English, but I can’t say I much enjoyed it. Like all of the other subjects on the curriculum, for the majority of the teachers, it was a case of “This is what you have to do to pass the exam.”

The school was around six miles from the Cavern in Liverpool, but the Mersey Poets, “Rubber Soul” and “Revolver”, may as well have never existed. I never even realised two of The Searchers and one of the Fourmost were former pupils till much later on, and the poems of that other famous “Old Boy”, Roger McGough, were passed around furtively, like quasi-pornographic threats to the establishment – which of course they were.

At least that’s how the Irish Christian Brothers viewed the world – this teaching order, at the heart of the Irish Rebellion, transformed in England into agents of the British state as they whacked their Irish working class pupils into the kind of middle class aspirants who would make it to university and thus justify our parents’ and grandparents’ decisions to emigrate.

It’s a strange approach to education, though not hard to see that our parents believed they were giving us the best possible start in life, and it’s one that caused me to operate in a completely opposite manner when I later became a happy and committed teacher for forty years or so.

Most of my school friends would agree with that jaundiced summation of our experiences, but I have tended to seek a more nuanced view. There is no doubt that the school was a soulless exam factory, and though a minority of teachers were truly inspirational, many pupils were damaged in varying ways by what could, be, at best, a stressful schooling, and, at worst, a scary, violent, demoralising education, which, to be fair, was not unusual in the sixties.

However, I am minded to acknowledge that the education I received got me to success in qualifications and a career which I have loved. I also made lifelong friends there and developed the ambition to become a teacher, so there were positives which it would be churlish to deny.

One of those was a Scottish teacher, Ernie Spencer, whose approach to English teaching in my last couple of years at school, was a breath of fresh air (he would have hated that cliché) and, in introducing to me to the War Poets, transformed my approach to poetry.

However, he was pushing at a door which had been opened, a couple of years before by two guys from Newark, New Jersey and Queen’s, New York: Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel.

In 1966, the usual English class poetry would be from Tennyson or Keats, and novels would be from HG Wells, R.M. Ballantyne or John Buchan. It was tedious, eye bleeding stuff – more to be endured than enjoyed.

Of course, outside of school, we were enjoying listening to the Beatles and the Stones and the Beach Boys, but, at that stage, they were delivering a “sound” – and one which could be quite indistinct on our transistor radios or Dansette record players, and the power of the lyrics was diminished by the overall driving beat, or by their very simplicity.

There’s nothing wrong with simple lyrics, of course – and the many hits produced in the Brill Building, based on teenage love and heartache, have retained a kind of innocent joy and resonance down through the decades.

The top ten in January 1966 contained “Day Tripper/We can work it out” by the Beatles, “Tears” by Ken Dodd and “The Carnival is Over” by The Seekers. There’s some indication of attention to lyrics there, but the Fabs were still mostly about sound and overall effect, and the latter two followed in a long tradition of superficial “moon in June” middle of the road lyrics.

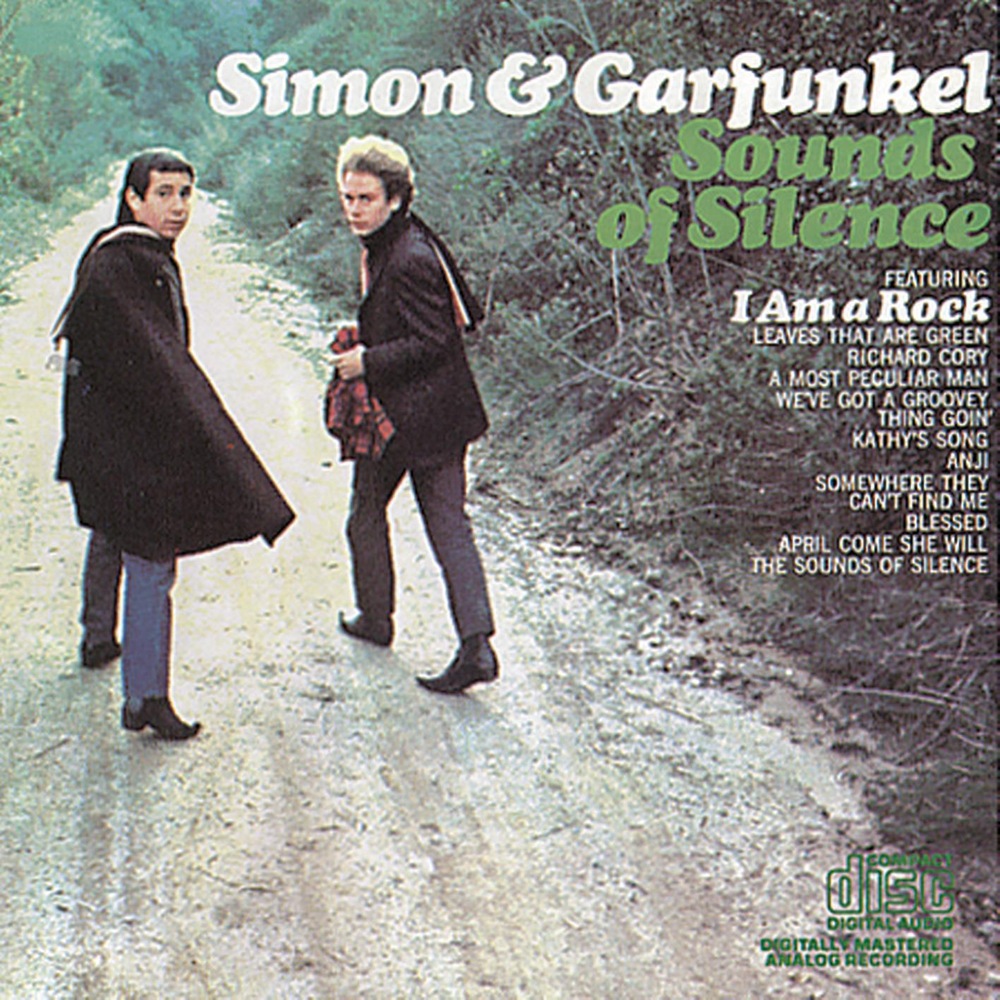

However, when “The Sounds of Silence” LP was released, fifty seven years ago this week, it was, to use present day parlance, a “game changer”. The production was crisp and the lyrics were easily as important as the music. In fact, when you stopped to listen – and increasingly we did – they were quite stunning.

The title track alone was full of lines which still resonate.

“Hello Darkness, my old friend” spoke to thousands of confused teenagers in lonely bedrooms trying to make sense of their lives. “Because a vision softly creeping, left its seeds while I was sleeping” was an image that even bored English students could access.

Then the song becomes cinematic: “narrow streets of cobblestone, ‘neath the halo of a streetlamp, I turned my collar to the cold and damp.” Impossible to hear those words without visualising the scene – from Humphrey Bogart to James Dean, and sensing the loneliness of adolescence, intensified by “my eyes were stabbed by the flash of a neon light”, an unwelcome and artificial intrusion.

The sense of alienation felt by so many adolescents, of being an outsider, is perfectly captured in “People talking without speaking, people hearing without listening, people writing songs that voices never shared. And no one dared disturb the sound of silence.”

“Silence like a cancer grows” is a message for the ages and another powerful piece of imagery, and we are back to that sense of being unable to communicate – in a beautiful painting of sound and vision: “But my words, like silent raindrops fell, And echoed in the wells of silence.”

One of the most prescient and visceral take downs of consumer madness is contained in “And the people bowed and prayed, to the neon god they made.”

And the final image can be filed under ‘once heard and seen, never forgotten’: “And the words of the prophets are written on the subway walls and tenement halls, and whispered in the sounds of silence.” I can still easily recall hearing those lines and understanding instantly – the answers are all around you if you only tale the time to look – which was a pretty seminal message for a fourteen year old.

Almost instantly, something clicked: this was how you could use words for effect, this was how imagery worked – to make an idea so powerful that you just had to imagine it.

No wonder then that when I heard Simon sing this at his Farewell Concert in Glasgow a few years ago, the tears flowed for the song that had meant so much to me as a fourteen year old.

The next track, “The Leaves that are Green” is more pop than folk, but still contains that appealing imagery of time passing, of which teenagers begin to gain an awareness as they look back and forward: “And the leaves that are green turn to brown, and they wither with the wind, and they crumble in your hand”. Love – the teenage obsession – is also deployed: “Once my heart was filled with the love of a girl, I held her close but she faded in the night, like a poem I meant to write.” It’s not difficult to imagine the Shakespeare of the sonnets and the Wordsworth of the nature poems producing these lines had they lived in the 1960s – and, of course, that was starting to open our minds to other forms of lyricism.

“Blessed”, with its biblical references, harmonies and jangling guitars could be described as “familiar” and then “Kathy’s Song” comes along to convince us further of the power of imagery: “I hear the drizzle of the rain, like a memory it falls” – an impressionist painting in words. “And from the shelter of my mind, through the window of my eyes” is a totally recognisable description of how we see the world, and the frustration of the teenager wanting to do so much but unable to do so is echoed in : “Writing songs I can’t believe, with words that tear and strain to rhyme,” as he missed his girlfriend who has remained in England as he returns to America. It would be a struggle to better the declaration of love: “I stand alone without beliefs, the only truth I know is you.”

We know that the girlfriend is Kathy Chitty, a girl from Essex, who was Simon’s muse when he was in England going round the folk clubs. She would appear again in one of his greatest songs “America”.

“Somewhere they can’t find me” is catchy pop and “Anji” is a folk club standard from Davey Graham – but here being introduced to a wider audience, and instilling in to many a desire to learn guitar.

The second side of the album starts with “Richard Corey” – more poetry – or at least a song based on a poem by Edwin Robinson, a nineteenth century American poet, and it is almost like the earlier songs have been preparing us for an actual poet as a follow on to poetic lyrics. Simon adopts a semi political stance, no doubt influenced by the songs from Greenwich Village at the time, and the lyric follows straightforward poetic scansion while managing to deliver lines of a style which were rare in “pop music” hits: “Born into society, a banker’s only child, he had everything a man could want, power, grace and style.”.

“A Most Peculiar Man” is classic Simon in that it combines the themes of loneliness and cinematic, almost documentary, description, reporting the suicide of a lonely man: “And Mrs Reardon said he had a brother somewhere, who should be notified soon” reflecting the anonymity of single life in a big city. The account of his loneliness was probably familiar to many teenagers who were not socially confident: “He lived, all alone, within a house, within a room, within himself.” The topic is huge, but the lyrics are simple and direct, especially the final sneer at the uncaring neighbours: “And everybody said ‘What a shame that he’s dead, but wasn’t he a most peculiar man.’”

You could almost believe that Simon and Garfunkel were leading us by the hand to accepting more formal poetry when you hear “April, Come she will”, a song that compares the changing of the seasons to a girl’s moods. There are lines that could be taken from the Romantic poets: “When streams are ripe and swelled with rain”, “In restless walks, she’ll prowl the night, July, she will fly, and give no warning to her flight”. It is easy to hear that this song, like “Anji”, and the later “Scarborough Fair”, is the result of the influence of the English folk clubs in which Simon had played and the style of singers like Martin Carthy and Bert Jansch.

“We’ve got a groovy thing going” was basically a tongue in cheek Everly Brothers pastiche to lighten the mood before the final song, again of loneliness and isolation, “I am a Rock”.

Although “The Sound of Silence” impressed us most creatively as fourteen year olds, it was undoubtedly this track which spoke to us most directly. It starts off softly and lyrically, with a guitar accompaniment: “A winter’s day, in a deep and dark December”, reminding us that alliteration was not a technique only employed by dead people! But then, with added instrumentation, the song slowly builds to a kind of frustrated yell at the world.

One of the conflicts of adolescence involves the need to be one of the group against the desire for privacy and individuality, and, more especially, the ability to choose when to be sociable and when to be lonesome. “I am a Rock” captures this conflict perfectly for teenagers.

It continues: “I am alone, gazing from my window, to the street below, on a freshly fallen, silent shroud of snow, I am a Rock, I am an Island.” These lines contain more than enough imagery, rhythm and rhyme to satisfy the most old fashioned of English teachers, but they are also defiant enough to take on the great poet John Donne, who famously wrote “No man is an island”.

But Simon is going in to bat for us disaffected teens.

When we have lost love or friendship, cannot get a girl or boyfriend, seek to be alone, we will not admit to being isolated. Our coping method will be to declare strongly that it is by choice – other folk are not ignoring or excluding me, I am choosing to be alone: “I’ve built walls, a fortress deep and mighty, that none may penetrate. I have no need of friendship, friendship causes pain, its laughter and its loving I disdain. I am a rock, I am an island.” You are not keeping me out, I am keeping you out. He is becoming angry, but not losing the lyricism or imagery.

Even more directly, he admits the reason for his anger: “If I never loved, I never would have cried” So that’s the answer, don’t risk the possibility of disappointment and heartache, be a rock that does not feel, and an island that cannot be reached.

He even goes on to push away any concern for him: “I have my books and my poetry to protect me, I am shielded in my armour, hiding in my room, safe within my womb, I touch no one and no one touches me. I am a rock, I am an island.”

No wonder we loved his words. He had put in lyrical form the great teenage shouts ”I am alright!” and “I don’t care!” – which, of course, mean the opposite.

And, just in case we have missed the point, he finishes with a strong emotional full stop:

“And a rock feels no pain. And an island never cries.”

He articulates an answer to that great adult-adolescent fault line:

“What have you got to be unhappy about?”

“Oh you just don’t understand.”

It is defiance – used as a coping mechanism and made lyrical.

He was giving us words to match our confused feelings, he was acknowledging how mixed up we felt, but he was also, more indirectly, pointing us towards the solace that can be brought by poetry and literature, the wonder of words, if you like.

And, all of a sudden, it became acceptable to like poetry, to have a go at writing it ourselves, to recognise that poets could be dead or alive, formal or free form in their writing, but could find the formula that would give articulation to our feelings and strength to our emotions. We could discuss lyrics, and, by extension, poems, it actually became a “cool” thing to do – and all the time we were honing our own communication skills, our creative abilities and our understanding of others and their feelings. We were learning to speak as well as talk, and listen as well as hear – to refer back to “The Sound of Silence”.

Later, “Homeward Bound”, written on Widnes railway station not twenty miles from our school, would underline the immediacy and reality of contemporary lyrics, while “America” would have us yearning for a journey across a country we had never visited.

Famously, producer Tom Wilson added the guitar, drum and organ arrangements to the title track and others without Simon and Garfunkel’s knowledge, and to their great displeasure, and it is true, to our ears, six decades later, some of the production sounds over wrought and clunky, but even that has its positive points.

This was still a time when a hit single sold an album and when the record labels were focussed on getting that top twenty radio hit, with an instantly recognisable “sound” and a “hook”. This was the reasoning behind Tom Wilson’s added production layer – to manufacture a hit record. It should be remembered that virtually all the tracks on “The Sounds of Silence” had been released by Paul Simon previously and sunk without trace in chart terms. What Wilson’s production did was to make the tracks “poppy” enough to attract radio attention and therefore increased sales. We may find the sound jars a little nowadays, but without that “pop” approach, we may never have been aware of these tracks. So it could be said that even the negatives about the recording turned out well in the end.

Emphatically, it is not an exaggeration to say that this album had a huge impact on my life – on how I saw literature, words, poetry, lyricism, imagery and all the magic techniques that would eventually become the tools of my trade as an English teacher.

More than that, of course, it opened the door to a whole developing genre of confessional singer songwriters: James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, Cat Stevens, Mary Chapin Carpenter, even down to Bruce Springsteen and Billy Joel – different styles but still producing lyrics which made you want to lie back, turn off the light and focus on the words and the pictures they painted. For long enough we had danced to the beat and thrilled to the sound, now we took in the words as well.

Paul Simon had opened a door for us and he would continue to usher us through it for the next fifty years – with or without Art Garfunkel, in myriad different styles and influences.

This album may have begun by introducing itself to Darkness as an old friend, but it finished by giving us the bright, light world of imagery and imagination, and an affection for the words which took us there.

To echo Roger McGough, late of our school: “Words? He could almost make them speak.”